| « The Nervous System is the New Battlefield: How AI Controls Your Mind | Big Pharma: The New Paperclip MKUltra Experiment » |

The Cancer Atlas: Mapping Humanity's Hidden Epidemic

Rick Foster

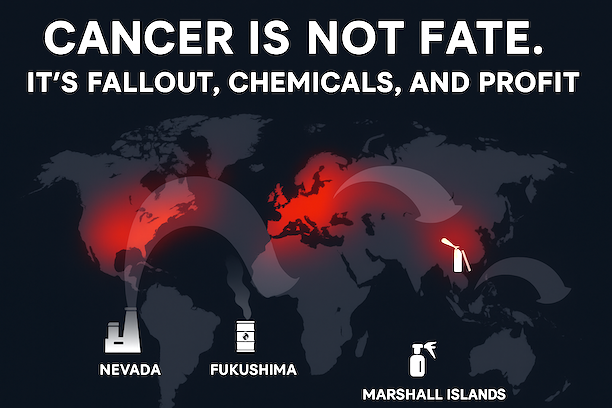

How chemicals, profit, and fallout made the cancer century

Introduction: Cancer Was Not Inevitable

Cancer has been discussed as if it's destiny, the grim shadow trailing the parade of human advancement to more life. But this is a myth. The data proves that cancer is not the backward-magical price of aging but the product of industrial choices-centuries of radiation experiments, chemical saturation, and the calculated trade of profit over prevention. Instead of unavoidable, cancer is the accidental legacy of a profitable industrialized world.

Western media often blames the diseased person for the sins of red meat and alcohol; it is dismissed as “cancer as fate/aging” via narrow narratives.

Globally, the numbers are staggering. In 2022 alone, more than 20 million people were newly diagnosed with cancer and nearly 10 million died (World Cancer Research Fund, 2022; American Cancer Society, 2024). The highest incidence rates no longer map neatly onto poverty or inadequate sanitation but onto the coordinates of industrial wealth: Western Europe, North America, and enclaves of Oceania lead the lists (World Cancer Research Fund, 2022). The disease is now a grim ledger of industrial advancement-recording where fallout scattered, where chemicals were sold, and where lifestyles shifted most extreme beneath the weight of processed foods, tainted air, and synthetic commerce.

The contribution of radiation from fallout is written in half-lives. The 1986 meltdown of the Chernobyl reactor dispersed radioactive isotopes across Europe, with fallout extending into Asia and detectable residues even in North America. Epidemiological projections estimate as many as 16,000 cancer deaths by 2065 from that single event (Cardis et al., 2006; International Agency for Research on Cancer [IARC], 2006). Fukushima's 2011 disaster, while less acute, released massive amounts of cesium and iodine into the atmosphere and oceans. United Nations reports concluded there would be no measurable population-wide increase in cancer, but millions of individuals across Japan and the Pacific were exposed against their will (United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation [UNSCEAR], 2013, 2020). Add to this the record of nuclear weapons testing-from Nevada to the Marshall Islands-and the picture is clear: the "peaceful atom" left a carcinogenic legacy that ignores borders.

The chapter on chemicals is equally incriminating. Air pollution itself has been classified by the International Agency for Research on Cancer as a Group 1 carcinogen, in the same company as asbestos and tobacco (IARC, 2013). Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), or "forever chemicals," were recently classified as carcinogenic to humans (IARC, 2023). Other well-known culprits-benzene, formaldehyde, paraquat-are prohibited or restricted in wealthy nations but still manufactured, sold, and sprayed across the developing world (Pesticide Action Network, 2023). The global economy's very structure ensures that those least able to manage toxins are subjected to the highest amounts.

Cancer thus tells a twin tale: of life years bought by industrial development, and of a plague created by that development. The global market in oncology drugs, already surpassing $200 billion annually, is projected to increase dramatically over the next ten years (IQVIA, 2023). Prevention, although demonstrated to be cheaper than treatment, remains a political afterthought (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD], 2020). And herein lies the greatest paradox of our time: a mostly preventable illness continues to increase, precisely because prevention interferes with the interests of commerce.

Cancer was not written into the human genome as destiny. It was manufactured into the modern condition. And unless history is read through this lens-through fallout clouds, chemical supply chains, and profit ledgers-the "cancer century" will be remembered not as an accident, but as a crime.

II. Cancer's Global Epicenters: Mapping the Modern Risk

Cancer is not random, nor is it evenly distributed. It clusters where industrialization, radiation exposure, and chemical proliferation intersect with population density and aging populations. According to the most recent figures available from GLOBOCAN 2022, the ten leading countries in numbers of new cancer cases are China, the United States, India, Japan, Russia, Brazil, Germany, France, the United Kingdom, and Italy (World Cancer Research Fund, 2022). Collectively, these nations account for nearly half of all new cancer diagnoses globally, reflecting geographic and industrial disparities that shape risk.

The Numbers That Tell a Story

|

Rank

|

Country

|

New Cases 2022

|

Population Context

|

Key Exposure Notes

|

|

1

|

China

|

4,824,703

|

Largest global population, rapid industrial expansion

|

Coal combustion, urban PM2.5, heavy chemical use

|

|

2

|

United States

|

2,380,189

|

Aging population, extensive industrial legacy

|

Hanford and Nevada Test Site fallout, PFAS, legacy asbestos

|

|

3

|

India

|

1,413,316

|

High population density, rapid urbanization

|

Coal air pollution, pesticide use, industrial solvents

|

|

4

|

Japan

|

1,005,157

|

Highly urbanized, aging population

|

Fukushima fallout, industrial chemical exposures

|

|

5

|

Russia

|

635,560

|

Industrial legacy, nuclear sites

|

Mayak/Kyshtym contamination, Chernobyl fallout, industrial solvents

|

|

6

|

Brazil

|

627,193

|

Urbanization, agricultural intensification

|

Agrochemicals, refinery emissions

|

|

7

|

Germany

|

605,805

|

Developed industrial economy

|

Chernobyl fallout, industrial dioxins, PCBs

|

|

8

|

France

|

483,568

|

Aging population, industrial sectors

|

Chernobyl fallout, industrial solvents, nuclear reprocessing legacy

|

|

9

|

United Kingdom

|

454,954

|

Industrialized, aging

|

Diesel PM2.5, legacy asbestos, nuclear test fallout

|

|

10

|

Italy

|

436,242

|

Urbanized and industrialized

|

Industrial PM2.5, chemical exposures, Chernobyl fallout

|

PM2.5 is particulate matter that is 2.5 micrometers or smaller in diameter-only about 30 times thinner than a human hair. Minute airborne particles, they are one of the largest contributors to air pollution and are found to be particularly dangerous because they have the ability to penetrate very deep into the lungs and even the bloodstream.

While high cancer numbers are linked with population size and detection capacity, they also reflect earlier exposure to radiological and chemical hazard. Japan and Russia demonstrate how nuclear accidents-Fukushima and Chernobyl-come together with industrial pollution to enhance threat. China and India are cases of quick industrialization with weak environmental regulation, increasing exposure to PM2.5, pesticides, and industrial chemicals (World Cancer Research Fund, 2022; American Cancer Society, 2024).

Patterns Beyond Numbers

They are not only bound together by case counts but by routes of exposure. Fallout from nuclear testing, combined with atmospheric and oceanic transport, has spread long-lived isotopes such as cesium-137 and strontium-90 across the Northern Hemisphere, including Europe, Asia, and North America (UNSCEAR, 2000; Cardis et al., 2006). Rich nations' prohibited chemicals like paraquat, formaldehyde, and legacy PCBs continue in use or persist in soils and aquatic habitats in these nations (IARC, 2013; Pesticide Action Network, 2023). Radiological background is overlaid by industrial activities, urban air pollution, and occupational exposure to yield an exacerbated risk environment.

Industrialization Meets Demography

World cancer map is therefore an industrialization account book: early industrializers and quick industrializers such as Germany, France, and United Kingdom have the aggregate burden of chemical exposure and fallout, whereas rapidly industrializing nations such as China, India, and Brazil acquire old exposures along with new exposures. Special cases are Japan and Russia, where nuclear accidents and manufacturing plants leave residual radiological hazard. These trends point towards a harsh truth: cancer is not merely a lifestyle or genetic issue-it is the radiological legacy of industrialization, environmental policy, and global trade (OECD, 2020; IQVIA, 2023).

III. Fallout That Doesn't Fade: Radiologicals, Bombs, and "Atoms for Peace"

The shadow of radiation is long and not visible. Although numerous chemical exposures travel a short distance, radioactive isotopes traverse vast distances from their source, adhere to soil and vegetation, and enter food chains feeding scores of generations. Pioneered in war, nuclear technology rapidly established a deposit of carcinogenic risk that ignores borders, decades, and political boundaries.

The Radionuclides That Define Risk

Certain isotopes enjoy a monopoly on public health concern due to their biological behavior and persistence:

• Iodine-131 (I-131): Short-lived, thyroid-banding, responsible for early thyroid cancers following nuclear testing and reactor accidents (UNSCEAR, 2000).

• Cesium-137 (Cs-137): Half-life ~30 years, it is sequestered in soils and forests, bioconcentrates in mushrooms, wildlife, and dairy (Cardis et al., 2006).

• Strontium-90 (Sr-90): Bone-sorbing, mimics calcium, and persists in soils and bones for decades (UNSCEAR, 2000).

• Plutonium-239/240: Millennia-long half-lives; sequesters in sediments and dust, with long-term occupational and environmental risks (IAEA, 2018).

• Noble gases and tritium: Short-term but diagnostic indicators of recent reactor effluent, providing evidence of environmental patterns of contamination.

These isotopes, although varying in immediate lethality, collectively describe a long-term burden of cancer risk that even now continues to manifest in exposed populations.

From Weapons to "Civilian" Reactors

The border between military and civilian nuclear activities has never been sealed. Atmospheric tests of nuclear weapons, from Nevada through Semipalatinsk, Novaya Zemlya, to the Pacific proving grounds, emitted cesium-137 and strontium-90 throughout the Northern Hemisphere (UNSCEAR, 2000). The 1953 "Atoms for Peace" initiative of Eisenhower further blurred boundaries, promoting nuclear energy utilization in civilian use but still maintaining supply chains for weapon-grade material (Eisenhower, 1953).

Case Studies of Nuclear Legacy

• United States: The Nevada Test Site put millions in exposure to I-131, especially in downwind communities; Hanford plutonium plants have polluted groundwater and soils, with reported elevations in local cancer incidence (NCI, 2021).

• Russia: The Mayak/Kyshtym complex produced one of the most disastrous peacetime nuclear accidents (1957), polluting the Techa River and leading to chronic radiation exposure for downstream villages (IARC, 2006). Chernobyl fallout contributed additional cumulative burden in western Russia.

• Japan: Nagasaki and Hiroshima remain reminders of wartime radiation, but the 2011 meltdown of Fukushima Daiichi rekindled the fear of cesium-137, iodine-131, and longer-term pollution of land and seafood (UNSCEAR, 2013; Buesseler et al., 2020).

Environmental Transport: Winds, Currents, and Food Chains

Worldwide spread of radiological hazards is supported by air and sea. The jet stream accounts for Chernobyl fallout across Europe within a few days, which fell in northern forests and alpine soils and continues to recycle into food supplies via forest fires and harvests (European Commission, 1987). Fukushima emissions headed east on the Kuroshio Extension into the North Pacific Current, blanketing radioactive cesium over thousands of kilometers and ultimately reaching parts of Hawaii, and North America (Buesseler et al., 2020).

Occupational and dietary exposures are risk-increasing. Doses are higher among liquidators, farmers, uranium miners, and nuclear reprocessing workers. Mushrooms, game, freshwater fish, and milk are some foods that act as bioaccumulators, lengthening and concentrating exposure over years.

The Unseen Century

The half-lives of the isotopes ensure that radiation's signature will endure the initial catastrophes. Cesium-137 will last for centuries, plutonium for thousands of years. The long-term durability ensures that Chernobyl and Fukushima will have lasting effects on human health and culture across generations, reshaping not only cancer rates but also environmental memory, land use, and regulation (Cardis et al., 2006; UNSCEAR, 2013).

IV. The Chemical Soup: Forbidden Poisons, Authorized Profits

Cancer is not inherited radiation but also cumulative chemical exposure. Globally, industrialization has generated a "chemical soup" in air, soil, water, and food. While some countries have prohibited or prohibited the most harmful substances, multinational companies still sell or discharge these chemicals to nations with less regulating oversight. This regulatory asymmetry sustains exposure and locks in cancer risk.

Regulatory Arbitrage: The Global Disparity

Many chemicals that are banned or heavily restricted in Western nations remain in use elsewhere. This phenomenon-regulatory arbitrage-turns weaker environmental laws into profit centers for industry. Examples include:

|

Chemical

|

Banned or Restricted In

|

Still Widely Used In

|

Primary Linked Cancers

|

|

Asbestos

|

EU, UK, Australia

|

US (partial), Russia, India, China, Brazil

|

Mesothelioma, lung, laryngeal, ovarian

|

|

Glyphosate

|

EU (heavily restricted)

|

US, Brazil, Argentina

|

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

|

|

Formaldehyde

|

EU/US (restricted in products)

|

Industrial manufacture in China, India

|

Nasopharyngeal, leukemia

|

|

Benzene

|

Strictly regulated globally

|

Legacy industrial sites in China, Russia

|

Leukemia

|

|

Paraquat

|

EU/UK

|

India, Brazil

|

Parkinsonism, various carcinogenic associations

|

|

Airborne PM2.5

|

Urban air regulations in EU/US

|

India, China, Brazil, Russia

|

Lung, bladder

|

|

Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) / Dioxins

|

Banned globally but persistent

|

Soil, water, and food in industrialized zones

|

Soft tissue sarcomas, liver, non-Hodgkin lymphoma

|

These chemicals are not inert. Persistent organic chemicals like PCBs and dioxins are kept in the soil and sediment for decades, entering the food supply in dairy, meat, and fish. Air particulates concentrate industrial heavy metals and hydrocarbons, entering city populations. Pesticides like glyphosate and paraquat have consistently been linked to hematologic cancers and neurodegenerative diseases (IARC, 2015; Pesticide Action Network, 2023).

Industrialization and chemical spread are inseparable. The first factory wave of power plants, chemical refineries, and factories came at the same time as the advent of chronic disease. Present-day export economies of industry-China, India, Brazil, and Russia-sustain both the historic legacy chemicals and the present agrochemical loads. Populations around refineries, crops sprayed with pesticides, and industrial hubs all suffer chronic low-dose exposure compounded across decades, insidiously increasing cancer incidence (World Health Organization [WHO], 2021).

Simultaneously, chemical companies in richer countries take advantage of the difference. DOMESTICALLY prohibited substances are legally shipped for other countries to use. This is not merely an epidemiologic public health emergency but also a moral crisis: cancer becomes a globalized product, outsourced to populations with less regulatory capacity, poorer access to healthcare, and less political power.

Cancer as a Manufactured Epidemic

Together, the prevalence of banned chemicals and unregulated exposures paints a stark picture: industrial-world cancer is, to a significant extent, preventable. The disease exists wherever economic profit takes precedence over human health. But subsequently, these same populations are sold expensive treatments, creating a tainted economic system where the causes of cancer are permitted-or even contracted out-to support a multi-trillion-dollar global oncology industry (IQVIA, 2023; OECD, 2020).

This poisonous cocktail, combined with radiological legacies, urbanization, and industrial effluent, creates a potent, additive risk environment. It is for this reason that the world map of cancer mirrors the flows of industrial capital, radiation fallout, and chemical commerce more than it does personal choice or heredity.

V. The Industrialization–Cancer Nexus: It's Not a Bug, It's a Feature

Cancer is not merely an offshoot of human biology; it is the shadow of industrial civilization. Globally, those nations that industrialized first and most thoroughly now have the highest cancer burdens. This correlation is not a coincidence-it is a foreseeable byproduct of chemical, radiological, and lifestyle exposures produced by industrial systems.

From Coal to Chemicals: The Historical Arc

Industrialization, beginning in the 19th century, was reliant upon coal, steel, and chemical manufacture. Coal burning released polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), arsenic, and heavy metals into urban air, and early chemical plants discharged solvents and carcinogens directly onto rivers and soil (Lauby-Secretan et al., 2018). Those living in industrial hubs had high levels of cancer, sometimes decades before modern epidemiology could identify the effect.

The Environmental Transition

As countries modernized, they underwent an "environmental transition." As demographics shift with urbanization and aging, exposure landscapes shift. Industrial pollution, the use of pesticides, and the production of chemicals followed at a rate faster than the regulatory systems could respond to them. The first industrialized nations-Germany, France, the United Kingdom, and the United States-exported commodities and risk. Later industrializers-China, India, Brazil, and Russia-built up a double burden: past chemicals from imports and domestic pollution (OECD, 2020; WHO, 2021).

Exported Risk, Outsourced Suffering

This new trend is reminiscent of a form of industrial colonialism. Toxics, wastes, and high-hazard chemical production are often exported from wealthier nations to nations with more lax environmental protections. Electronics dumping in India and Bangladesh, Chinese e-waste dumps in landfills, and pesticide cultivation in Brazil are just a few examples of how toxic risk is outsourced. Receiving societies are "manufactured victims," posing long-term cancer risk without matching health infrastructure (Pesticide Action Network, 2023; WHO, 2021).

Industrialization as an Enabling Feature, Not a Bug

In this view, cancer is not an accident of statistics; it is an emergent characteristic of industrial capitalism. Systems were designed to generate maximum output and profit with little regard for long-term health consequences. The recurrence of carcinogens-chemical, particulate, or radiological-insures populations will continue to develop cancer at rates that can be predicted. Industrialization, rather than being an indifferent factor, actively generates the global cancer map.

The Profit Paradox

The economic basis built on cancer further complicates the problem. Multinational pharma, private hospitals, and medical technology industries make the most money from cure, rather than prevention. This creates a perverse feedback loop: environmental toxins persist, exposures continue, and cancer incidence guarantees a sure bet market for expensive interventions (IQVIA, 2023). Prevention efforts, however, are underfunded, politically inconvenient, and provide no near-term payoff.

Ultimately, industrialization created both the risk and the market for its avoidance. Cancer is the bug feature, not the bug, of the industrial system-a disease that has been created by past and present policy decisions, sustained by loopholes in regulation, and profited from by the medical-industrial complex.

VI. The Trillion-Dollar Treatment Trap: Why Prevention Is Ignored

Whereas industrialization creates hazard, a twin system exploits illness. The global oncology market today is over $200 billion annually and is projected to reach more than $500 billion by 2030 (IQVIA, 2023). Under these circumstances, cancer is not merely a matter of public health but also an economic force, paying the maintenance of hazard rather than its elimination.

The Business of Cancer

Pharmaceutical firms, private healthcare facilities, and medical technology firms are the ones that benefit most from late-stage treatments. New chemotherapies, immunotherapies, and targeted biologics generate tremendous profit margins, particularly among upper-income countries where insurance and government subsidies guarantee reimbursement (IQVIA, 2023). Advanced medical imaging-MRI, CT, PET, and radiation therapy devices commodifies disease management even more.

Conversely, prevention programs are deliberately underfunded. According to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD, 2020), less than 10% of global cancer research spending is allocated to environmental, chemical, and radiological prevention. Public health campaigns, city clean air, and agricultural worker safety are similarly underfunded relative to treatment following diagnosis. This disparity is political and economic incentive: prevention reduces incidence and therefore reduces the certain market for costly interventions.

Prevention Is Unprofitable

Chronic industries such as chemical and industrial industries, and medical technology manufacturers, indirectly gain from chronic exposure. Air pollutants, agrochemicals, and industrial solvents continue to be produced in industrial and developing nations. Regulation is random and piecemeal. Industry claims exposures to be "within safe limits" but the limits are themselves determined sometimes on economic, as opposed to health, calculations (WHO, 2021). Through this means, cancer is preserved as a sellable result of poor regulation and costed-out underinvestment in prevention.

A Century of Externalized Costs

This is a system that externalizes socially and geographically. Populations in high-industrializing nations-China, India, Brazil, and parts of Russia-receive exposures without universal treatment access (Pesticide Action Network, 2023; WHO, 2021). Rich countries, on the other hand, deliver chemicals and high-cost technologies for export. The result is a globalized health inequality: cancer cases are produced here, treated there, and capitalized over borders.

The Moral Paradox

The paradox at the core is glaring: billions of dollars annually are spent curing a disease that is dominantly preventable. Industrialization, regulatory loopholes, and profit interests all conspire to render prevention politically inconvenient and economically undesirable. The system ensures that risk persists, exposures accrue, and markets remain healthy. In short, cancer is not only caused by chemicals and radiation but also by the architecture of wealth and policy that dictates whose health to protect and whose to give away.

VII. The Illusion of Progress: Cancer's Entrenchment in Advanced Societies

The ideal of a "way forward" to cancer prevention is myth. Regulatory mechanisms, designed first to lower chemical, radiological, and industrial hazards, are being dismantled or sabotaged globally. Deregulation, under the guise of economic advancement and "innovation," accelerates exposure to proven carcinogens, ensuring the most industrially advanced societies the highest, longest cancer burdens.

Deregulation as Acceleration

In the United States, chemical safety regulations, air quality standards, and pesticide registration have continuously relaxed. Well-known PFAS chemicals are stable and continue to be carcinogenic and still contaminate water systems at levels previously considered unacceptable (IARC, 2023). Glyphosate, benzene, formaldehyde, and industrial solvents are more generally accepted under diluted systems of enforcement, and workplace protection lags behind technological dissemination (Pesticide Action Network, 2023; WHO, 2021).

Europe, traditionally a bastion of chemical control, is under the pressure of trade agreements and industry lobbies and, consequently, long delays and diluted bans, and weakening enforcement. Japan, Russia, and China continue to have Cold War heritage radiological fallout from Chernobyl, Fukushima, and Mayak supplemented by ongoing industrial emissions. Urban air pollution, PM2.5 particulate matter, and persistent organic pollutants are part of daily life, invisible but relentless (Cardis et al., 2006; Buesseler et al., 2020).

Industrial Interests Supersede Health

World industrial, chemical, and Agro-food networks have coalesced to perpetuate exposure and commodify the consequences. Carcinogenic commodities remain lucrative as prevention is expensive, politically unviable, and ultimately unremunerative. Health authorities document risk but regulatory complacency in conjunction with corporate lobbying ensures partial mitigation. The "cancer century" is not a result of failure in regulation-but an emergent property of policy making to maximize profit over public health (IQVIA, 2023; OECD, 2020).

The Cultural Imprint of Persistent Risk

Cancer will not only define individual mortality but also redefine culture. Highly industrialized societies with deregulated chemical environments will learn to make cancer a normal cost of modern living. Early exposures, work-related hazards, and pollution will create health consequences across several generations. The map of risk captures the patterns of capital flows and industrial production, creating geographic and social disease stratification that will be entrenched for decades (WHO, 2021).

The Inevitability of a Manufactured Epidemic

Chemicals, radiation, and industrial food systems meet to provide an ongoing, widening epidemic. Where "advanced" countries were once believed to have disease under control, deregulation assures their populations will continue to be acutely at risk. Cancer is no longer a remote threat or a random accident; it is a built-in element of modern industrial existence. The most technologically and economically "advanced" nations-those that led the way in chemicals, the atom, and industrial growth-will be most likely to bear the heaviest, most normalized loads.

No hero rides to the rescue. No social movement, no technological fix, no regulatory reformation saves the day. The trajectory is mapped: the cancer century marches on, inscribed into policy, trade, and culture, spanning centuries in relentless predictability.

VIII. The Century of Manufactured Cancer

Cancer is now not only a disease but also the seal of an industrialized world. Radiation, chemical proliferation, and unregulated food and bio-industries have combined to produce an environment in which cancer is the norm, expected, and commodified. The trends are obvious: the oldest and most technologically advanced societies, who initially set the pace in industrialization, chemical manufacturing, and nuclear energy, now suffer the most intense and most persistent disease burdens.

Evidence is unflinching. Nuclear test and accident atmospheric fallout-Los Alamos, Chernobyl, Fukushima, Nevada, and the Marshall Islands-peaks in soils, forests, and oceans, bequeathing a multigenerational carcinogenic legacy (UNSCEAR, 2000; Cardis et al., 2006; Buesseler et al., 2020). Forbidden chemicals in wealthier nations hang around in poorer nations, and deregulation continues to accelerate exposure even among previously protected populations (IARC, 2023; Pesticide Action Network, 2023). Air particulate matter, industrial solvents, and persistent organic pollutants intersect with life-style and food variables to form a cumulative, unavoidable risk (WHO, 2021).

This is no act of nature. This is an epidemic engineered by regulatory breakdown, by industrial lobbying, and by an economic model that turns treatment into a commodity and ignores prevention. Populations are exposed intentionally or negligently, and cancer is the inevitable outcome. The cycle is self-perpetuating: risk generates market demand, market demand legitimates risk, and public health is eroded in the bargain.

Today, cancer is no longer an accident that happens to individuals; it is the anticipated consequence of industrial society itself. The world's most "advanced" nations, makers of chemical, nuclear, and bio-industrial expansion, now live in environments saturated with carcinogenic risk. Society's highest technological and economic achievements have been accompanied by a comparable astonishing epidemic increase of disease.

The age of industrial-induced cancer continues, and no horizon of prevention, intervention, or respite appears on the horizon. The human health, culture, and memory have become intertwined with the forces of industry that created this pandemic. Cancer's geography is industrial society's geography, and its shadow will be seen through current and future generations.

Sources

- American Cancer Society. Global Cancer Facts & Figures 2024.

- Buesseler, K., Aoyama, M., & Fukasawa, M. Fukushima-derived radionuclides in the Pacific Ocean. Science of the Total Environment, 714, 136738.

- Cardis, E., et al. Estimates of the cancer burden in Europe from radioactive fallout after the Chernobyl accident. International Journal of Cancer, 119(5), 1224–1235.

- Eisenhower, D. D. Atoms for Peace speech. U.S. Department of State, 1953.

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. Monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans: Some organophosphate insecticides and herbicides. 2015.

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. Outdoor air pollution a leading cause of cancer. IARC Monographs, 2013.

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. Health effects of the Chernobyl accident. IARC Monographs, 2006.

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. Monographs on per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), 2023.

- International Atomic Energy Agency. Environmental remediation of plutonium contamination, 2018.

- IQVIA. Global oncology spending and market trends, 2023.

- Lauby-Secretan, B., et al. Carcinogenicity of industrial processes and pollutants. The Lancet Oncology, 19(8), e405–e406, 2018.

- National Cancer Institute. Radiation and cancer: Downwinders and Hanford site exposures, 2021.

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. Environmental and health investment disparities, 2020.

- Pesticide Action Network. Global pesticide usage and regulatory disparities, 2023.

- United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation. Sources and effects of ionizing radiation. UNSCEAR Report to the General Assembly, 2000.

- United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation. Fukushima accident report, 2013.

- World Cancer Research Fund. Global cancer data by country. GLOBOCAN 2022.

- World Health Organization. Air pollution and health: Global exposure estimates, 2021.

###

The Cancer Atlas: Mapping Humanity's Hidden Epidemic

Rick Foster