| « Russian Ukraine War Summer 2025 Update | A Cry for the Arctic: The Plunder of Earth's Last Wild Sanctuary » |

Criminals, Cartels, and Corporations: The 20 Worst Pillagers of the Amazon & Orinoco

Fred Gransville

I. Introduction

The Lungs of the Earth Are Being Stabbed from All Sides

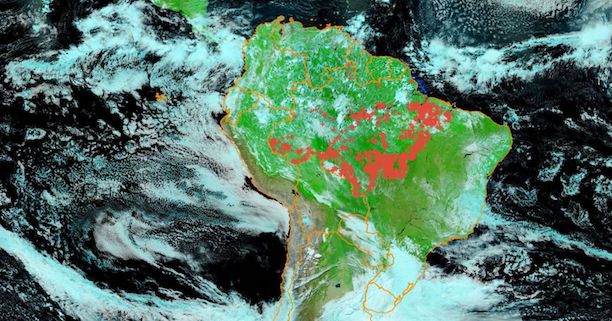

In June 2025, the Amazon and Orinoco basins—twin arteries of South America's ecological soul—are hemorrhaging under a coordinated assault. These are not isolated crimes of negligence. They are acts of premeditated ecocide, orchestrated by cartels, corporations, and complicit governments who regard ancient forest not as sacred biome, but as expendable inventory. Despite international pledges, ESG audits, and viral documentaries, the rate of destruction has accelerated, not slowed. The world’s largest rainforest, once home to a fifth of all terrestrial species, is careening toward irreversible collapse.

The Amazon lost over 1,500 square miles of forest in the first five months of 2025 alone—an area larger than New York City—with fires starting earlier and burning longer due to El Niño–driven drought and the rollback of land protections in frontier states like Pará and Rondônia (Associated Press, 2025a; INPE, 2025). Meanwhile, to the north, the Orinoco River basin—a system rarely mentioned in global headlines—is suffering a parallel catastrophe. Venezuela’s criminal mining economy, centered in the so-called Arco Minero del Orinoco, has turned once-pristine rivers into chemical morgues, laced with mercury, cyanide, and crude oil (RAISG, 2024; Global Witness, 2024).

What is happening is not simply deforestation—it is terraforming. The Amazon is approaching the critical tipping point, estimated between 20 and 25 percent forest loss, beyond which it may no longer sustain its own hydrological cycle and will transform into savanna. As of 2025, 18 to 19 percent of the rainforest has already been destroyed (Nobre et al., 2025; Lovejoy & Nobre, 2021). This transformation would not only extinguish thousands of endemic species—it would also release over 90 billion tons of carbon, undermining any remaining hope of climate stability.

Behind these statistics are names—some infamous, others hidden behind shell corporations and military uniforms. This article exposes the 20 worst offenders behind this twin-ecosystem collapse, drawing from field investigations, deforestation alert systems, leaked documents, and Indigenous testimonies. From illegal timber lords to agribusiness exporters, mining mafias to state-sanctioned looters, these actors represent a global failure not merely of policy, but of moral imagination.

As Brazil’s Minister of the Environment Marina Silva declared bluntly in a June 2025 interview: “We are already at the limits of a livable climate. The Amazon’s destruction is no longer an environmental issue—it is a civilizational one” (Time, 2025).

II. The Worst Offenders: Profiles in Ecocide

The destruction of the Amazon and Orinoco is not a random byproduct of “development.” It is a deliberate campaign—greed weaponized as governance, extraction rebranded as progress. These twenty entities represent the worst environmental and moral offenders driving two of Earth’s greatest biomes toward collapse.

1. Primeiro Comando da Capital (PCC) – The Narco-Miners of the Amazon

Once confined to Brazil’s prison system, the Primeiro Comando da Capital (PCC) has metastasized into the dominant armed cartel inside the Brazilian Amazon. In 2024 and 2025, the PCC consolidated control over hundreds of illegal gold mining (garimpo) sites across Roraima, Pará, and Amazonas, particularly inside Indigenous territories like the Yanomami and Munduruku reserves. These operations use dynamite, backhoes, and dredging rafts to scar riverbeds and poison entire watersheds with mercury (RAISG, 2024; Mongabay, 2024a).

The PCC’s incursion into Yanomami land has led to the deaths of over 500 children since 2020 from mercury poisoning, malnutrition, and untreated malaria (Survival International, 2024). Despite high-profile military raids, satellite imagery from early 2025 reveals over 1,200 active mining sites—most abandoned only temporarily, then reoccupied days later (Amazon Conservation Association, 2025).

As one Indigenous elder told El País, “We no longer hear birds. The river is sick. The gold comes out, but our children die.”

2. Chaules Volban Pozzebon – The Logging Lord of Northern Brazil

In 2024, Chaules Volban Pozzebon was convicted as the head of one of the largest illegal timber syndicates in Brazil’s history—overseeing more than 120 clandestine sawmills funneling high-value hardwoods like ipê and mahogany to foreign markets. Federal prosecutors linked him to an estimated 80,000 hectares of illegal deforestation between 2016 and 2023 (Brazilian Federal Police, 2024).

Pozzebon’s empire spanned the states of Acre, Rondônia, and Mato Grosso, where bribes, violence, and fake land titles (grilagem) were used to launder stolen forest as "legal timber" through shell companies. In one intercepted message, Pozzebon allegedly bragged: “The forest is endless. And so is the demand.”

Sentenced to 99 years for environmental crimes, racketeering, and money laundering, Pozzebon remains a symbol of Brazil’s ongoing struggle to rein in industrial-scale environmental crime.

3. JBS S.A. – The Meat Empire That Feeds on Forests

JBS S.A., the world’s largest meatpacker, has long denied responsibility for Amazon deforestation. Yet evidence from satellite audits, supply-chain investigations, and whistleblower documents paint a darker picture. As of 2025, JBS-linked suppliers continue to be exposed for sourcing cattle from embargoed or illegally cleared lands in Pará, Mato Grosso, and Rondônia (Mighty Earth, 2025; Greenpeace, 2024).

Reports from 2024 show that between 28,000 and 32,000 hectares of deforestation per year can be linked—directly or indirectly—to JBS’s beef supply chain, despite “zero-deforestation” pledges (Global Witness, 2024). Investigations also reveal that cattle laundering—the practice of transferring livestock between farms to hide illegal origins—remains widespread. Boycott Beef, your heart will thank you by lasting 10-20 years longer.

JBS has become the face of a global hypocrisy: companies claiming environmental stewardship while fueling ecocide with every steak exported.

4. Garimpeiros of Sararé – The Gold Rush That Burns the Forest

In Santarém, Santarita, and Sararé, waves of illegal gold miners—often referred to as garimpeiros—have invaded remote areas, sometimes in organized units numbering in the thousands. By 2025, over 5,000 miners were active in the Sararé Indigenous Territory alone, guarded by armed militias and operating under cover of darkness (Amazon Watch, 2025).

The resulting mercury pollution has sterilized entire rivers, while clandestine airstrips and money laundering through fake cooperatives have made prosecution nearly impossible. Mercury bioaccumulation is now detectable in 80 percent of local fish samples, rendering traditional food sources toxic (Instituto Socioambiental, 2025).

These mining mafias are not rogue actors—they are the petrochemical plague of the Amazon’s waterways, corroding life from within.

5. Harley Sandoval & the Gold Export Scam

In a landmark forensic investigation in early 2025, Brazilian officials used “gold-DNA” technology to trace the origin of 294 kilograms of gold falsely claimed to be legal. The gold, worth over $18 million, was linked to Harley Sandoval, a logistics tycoon operating out of Manaus who ran a chain of export firms and refineries with falsified paperwork and phantom cooperatives (Reuters, 2025; The Intercept Brasil, 2025).

This case exposed one of the largest laundering schemes in Amazon gold history. With funding connections to international banks and ties to the UAE and Switzerland, Sandoval’s network represents the financial dimension of rainforest destruction—clean gold on the outside, blood and mercury on the inside.

As analysts noted, “The Amazon is not just being destroyed with chainsaws and dredges. It is being erased with spreadsheets and shipping containers.”

6. Cassiterite & Critical Mineral Mafias – The ‘Black Gold’ Gangs of Roraima

The next mining frontier is not gold—but cassiterite, niobium, and rare earth minerals. In northwestern Brazil, criminal factions now compete over cassiterite (tin ore), essential to electronics and solar tech. These "black gold" operations—many fronted by corrupt cooperatives—have invaded Indigenous territories, including Yanomami and Macuxi lands, using clandestine helicopters, river dredgers, and militarized encampments (Instituto Socioambiental, 2025; Mongabay, 2024b).

Recent seizures in 2025 by IBAMA revealed over 22 metric tons of illegally mined cassiterite being funneled to Europe and Southeast Asia, often mislabeled through Bolivian intermediaries. Rivers near Boa Vista now test positive for both mercury and lead, a dual neurotoxic threat to aquatic and human life.

These mafias mark a shift in Amazon destruction—from traditional logging and beef to next-generation resource wars, disguised as “clean energy” progress.

7. Maduro’s Mining Arc – Venezuela’s State-Sanctioned Ecocide

Launched in 2016, the Arco Minero del Orinoco is a 92,000-square-kilometer “development zone” that now constitutes Venezuela’s single largest environmental crime. Under President Nicolás Maduro, the region has become a free-for-all for illegal gold, diamond, and coltan mining—devastating forests near Canaima National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site (RAISG, 2024; Human Rights Watch, 2024).

Reports from late 2024 and early 2025 confirm that military units and paramilitary proxies (known as “syndicates”) are taxing mining operations in exchange for protection. These groups deploy child labor, enforce curfews, and use violence against Indigenous peoples such as the Pemón and Sanemá (Global Witness, 2024).

More than 500 Indigenous people have reportedly been killed or disappeared since the project’s inception. Satellite imaging shows deforestation expanding by 1,300 square kilometers per year, with over 70 percent of mines located in protected zones (Amazon Geo-Referenced Information Network [RAISG], 2024).

This is not merely corruption. It is state-engineered ecocide, cloaked in nationalist rhetoric and financed by transnational mining syndicates.

8. Paramilitary and Guerrilla Networks – ELN and FARC 2.0

Across the Orinoco basin in Colombia and Venezuela, armed groups including the Ejército de Liberación Nacional (ELN) and FARC dissident factions have rebranded as environmental destroyers. These groups fund themselves by controlling gold mining routes, timber corridors, and drug smuggling trails deep in the jungle (Crisis Group, 2025; Insight Crime, 2025).

In the Llanos Orientales and Guainía regions, guerrilla roadblocks now control access to riverbanks where illegal dredging occurs. Environmental watchdogs estimate that more than 40 percent of illegal mining zones in Colombia’s Amazon are under guerrilla or paramilitary control. The Colombian military, itself under scrutiny for human rights abuses, has been unable—or unwilling—to confront these shadow regimes (Crisis Group, 2025).

The result is a brutal convergence: narco-conflict economics fused with ecosystem annihilation.

9. Agribusiness Giants – Cargill, Bunge, Marfrig, and Bayer-Monsanto

Despite glossy ESG brochures and high-profile pledges, agribusiness giants like Cargill, Bunge, Marfrig, and agrochemical titan Bayer-Monsanto remain deeply enmeshed in the deforestation economy. These companies dominate soy and beef exports sourced from lands often illegally cleared in the Amazon and Orinoco frontier zones (Greenpeace, 2024; Trase, 2025).

Bayer-Monsanto’s genetically modified (GMO) soybeans—engineered for herbicide tolerance—have enabled industrial-scale monocultures reliant on heavy applications of glyphosate and other toxic pesticides. This agrochemical cocktail has devastated soil health, wiped out aquatic biodiversity through runoff, and caused widespread health problems in local communities (Mongabay, 2025; Survival International, 2025).

In 2024, Trase Earth traced over 100,000 hectares of deforested land in Paraguay, Bolivia, and western Brazil directly linked to these companies’ supply chains. The pattern involves indirect suppliers and “clean-up” farms that obscure the illegal origins of cattle or soybeans—known as “reverse laundering.”

As one Indigenous leader in Mato Grosso lamented, “The forest dies not just from chainsaws, but from poisons flowing in our rivers.”

10. Venezuelan Oil Palm Expansion – The Orinoco’s Monoculture Invasion

In Venezuela’s Amazonas and Bolívar states, oil palm plantations—many owned by military-linked conglomerates—are replacing biodiverse forest with monocultures stretching across the horizon. Particularly in the Meta region near the Colombia border, aerial surveys from 2025 show over 60,000 hectares of recent palm expansion, some directly overlapping Sikuani and Piaroa Indigenous territory (Amazon Conservation Team, 2025).

Oil palm is lauded by the Maduro government as an “economic alternative” to mining and petroleum. In practice, it is a biodiversity graveyard. These plantations drain water tables, offer no habitat for native fauna, and are laced with glyphosate and paraquat pesticides that contaminate river systems (Survival International, 2025).

Far from “green development,” this monoculture boom is a carbon-intensive shell game, trading one form of devastation for another—only this time, in government-approved rows.

11. Hydropower Megaprojects: Belo Monte and Tapajós Dams

Brazil’s hydropower ambitions have wrought devastating consequences. The Belo Monte Dam on the Xingu River displaced more than 40,000 people, primarily Indigenous communities, flooding vast tracts of rainforest and disrupting aquatic biodiversity (International Rivers, 2024). Methane emissions from decomposing vegetation behind the dam now contribute significantly to greenhouse gases, undermining hydropower’s green credentials (Guan et al., 2025).

Proposed Tapajós Basin dams—intended to supply electricity for mining and agriculture—threaten the Munduruku Indigenous lands, a cultural and ecological treasure. These projects block migratory fish like the endangered giant catfish (Brachyplatystoma filamentosum), which sustain both ecosystems and local diets (IBAMA, 2025).

Hydropower here is a double-edged sword: while touted as renewable energy, it is simultaneously an instrument of ecological destruction and social displacement.

12. Illegal Coal Mining in La Guajira, Colombia

Nestled at the northern edge of the Amazon-Orinoco nexus, Colombia’s La Guajira region has seen a surge in illegal coal mining that ravages forest cover and pollutes water sources. Illegal operators, often linked to paramilitary groups, clear-cut native vegetation, contributing to soil erosion and the collapse of local ecosystems (CIFOR, 2025).

Communities report chronic respiratory illnesses attributed to coal dust, while artisanal miners face exploitation and hazardous conditions. Despite government crackdowns, corruption and impunity persist, making La Guajira a hotspot of environmental injustice (Human Rights Watch, 2024).

13. Pulpwood Plantations: Suzano and Fibria’s “Fake Forests”

Brazilian pulp giants Suzano and Fibria have replaced thousands of hectares of biodiverse rainforest with monoculture plantations of eucalyptus and pine, creating ecological deserts bereft of wildlife (Mongabay, 2025).

These plantations consume vast quantities of water, lowering groundwater levels and exacerbating drought conditions. While marketed as “reforestation,” such plantations do not replicate the carbon storage or habitat functions of native forests (Amazon Conservation Team, 2025).

Critics describe this model as “greenwashing at scale,” trading ecological integrity for paper profits.

14. Oil Spills and Negligence by PDVSA in the Orinoco

Venezuela’s state oil company, PDVSA, is responsible for chronic pollution in the Orinoco basin. Frequent pipeline ruptures have spilled crude into vital waterways like the Guarapiche River, contaminating fish populations and poisoning communities (Global Witness, 2024).

Environmental oversight has collapsed amid Venezuela’s ongoing crisis, allowing spills to go unremediated for months. Indigenous groups such as the Warao report increased cancer rates and birth defects linked to water contamination (RAISG, 2024).

PDVSA’s negligence exemplifies the entanglement of extractive industries and environmental catastrophe in the Orinoco.

15. Financial Enablers and Money Laundering Networks

Behind the physical devastation lies a shadow economy fueled by financial institutions and shell companies in the United States, Europe, and offshore tax havens. Investigations by the FACT Coalition and Transparency International reveal how illegal gold and timber profits are laundered through complex networks, financing further deforestation and violence (FACT Coalition, 2025; Transparency International, 2024).

Major global banks have been implicated in ignoring “red flags,” knowingly processing transactions linked to Amazonian crime syndicates. The flow of illicit capital perpetuates a cycle of lawlessness and impunity, undermining enforcement efforts on the ground.

Efforts to implement gold-DNA traceability and deforestation-linked financial regulations have begun, but enforcement remains inconsistent.

16. Soy Expansionists in Bolivia and Paraguay: Bayer-Monsanto’s Chemical Footprint

In Bolivia’s Santa Cruz and Paraguay’s Alto Paraná, the soy agribusiness boom is inseparable from the pervasive use of Bayer-Monsanto’s GMO seeds and associated pesticides. Large producers like Los Grobo rely on these inputs to sustain yields on recently deforested lands, often cleared through slash-and-burn methods (Mongabay, 2025; WWF, 2024).

These herbicide-tolerant soy monocultures generate massive quantities of chemical runoff, contaminating groundwater and rivers feeding into the Amazon and Orinoco basins. The ecological consequences include loss of amphibians, fish die-offs, and long-term soil degradation, imperiling the region’s resilience to climate change (INPE, 2025).

Communities downstream report rising cancer rates and birth defects consistent with pesticide exposure, yet regulation enforcement remains lax under local governments complicit in the agribusiness model.

17. Cattle Ranchers in Colombia’s Llanos: Fire, Expansion, and Chemical Runoff

In the Llanos Orientales, vast cattle ranching operations continue to expand aggressively, converting wetlands and forest edges into pasture. Ranchers frequently use fire as a land-clearing tool, intensifying greenhouse gas emissions and regional haze (FAO, 2024).

Moreover, many ranchers rely on glyphosate-based herbicides—primarily sourced from Bayer-Monsanto products—to suppress invasive vegetation and maintain pasture monocultures. Runoff from these chemicals seeps into adjacent waterways, compounding the ecological damage with contamination that affects aquatic life and local communities (Survival International, 2025).

Paramilitary groups linked to land grabs often provide the muscle behind this expansion, leading to violent evictions of Indigenous peoples such as the Sikuani and Curripaco (Crisis Group, 2025).

18. Artisanal Coltan and Tantalum Miners: Toxic Extraction Amid Biodiversity Hotspots

The extraction of coltan—critical for electronics manufacturing—has surged in the Venezuelan Amazon and Orinoco basin, often carried out by artisanal miners with little oversight (Global Witness, 2024). These miners disrupt river sedimentation patterns, exacerbating mercury contamination—a chemical already widespread due to gold mining.

Though not directly linked to agrochemicals, this mineral rush intersects with deforestation patterns created by agribusiness expansions, where Bayer-Monsanto’s GMO crops push frontier clearing further into intact forest.

19. Illegal Logging Syndicates in Madre de Dios, Peru: Forests Lost, Poison Spread

In Peru’s Madre de Dios, illegal logging for valuable species like rosewood and mahogany continues unabated, driven by transnational demand (WWF, 2025). These operations also coincide with upstream soy and palm expansions—both heavily dependent on glyphosate and other Bayer-Monsanto pesticides—which degrade soils and increase forest vulnerability (Peruvian Ministry of Environment, 2025).

The combined pressure of logging and agrochemical runoff threatens rare species and intensifies conflicts with Indigenous communities defending their ancestral lands.

20. Coca Cultivation and Deforestation in Colombia: A Toxic Frontier

Colombia’s Amazon remains a battleground where illegal coca cultivation, narcotrafficking, and agribusiness collide. Coca farms are established by clearing primary forest, and aerial fumigation campaigns use glyphosate-based herbicides—originally developed by Bayer-Monsanto—to destroy crops, causing collateral damage to surrounding ecosystems and communities (UNODC, 2024).

Though fumigations aim to reduce narcotrafficking, the environmental and health costs are high, including loss of biodiversity and increased chemical exposure for Indigenous and peasant populations.

Conclusion

The destruction of the Amazon and Orinoco basins is no longer an abstract environmental issue; it is an accelerating, multifaceted crisis with profound geopolitical, ecological, and moral implications. The twenty worst offenders—ranging from violent cartels and rogue paramilitaries to multinational corporations and complicit state actors—operate within a complex system that sustains and deepens this devastation. Their actions have pushed these ecosystems perilously close to irreversible tipping points, threatening biodiversity, carbon storage capacity, and the traditional ways of life of Indigenous peoples.

The geopolitical dimension is equally fraught. The Amazon and Orinoco have become theaters where illicit economies intersect with state failures, corruption, and international market demands. This nexus of criminality and corporate exploitation exacerbates regional instability and undermines global climate goals. Meanwhile, Indigenous communities continue to resist these incursions, asserting sovereignty and environmental stewardship despite facing violence and political marginalization. However, governmental efforts remain insufficient and often counterproductive, revealing systemic governance failures that perpetuate the cycle of destruction.

For concerned individuals, meaningful engagement begins with informed support and advocacy. Contributing to or amplifying the work of organizations dedicated to preserving these vital ecosystems can create pressure and resources necessary for change. The following organizations are widely recognized for their effective and transparent work against Amazon and Orinoco ecocide:

- Amazon Conservation Team (ACT) – Works closely with Indigenous communities to protect rainforest biodiversity and Indigenous land rights through participatory mapping and sustainable development programs (Amazon Conservation Team, 2025).

- Survival International – Advocates globally for the rights of Indigenous peoples, exposing violence and land dispossession while supporting Indigenous-led conservation efforts (Survival International, 2025).

- Rainforest Foundation US – Provides legal aid and supports Indigenous organizations fighting illegal deforestation and resource extraction (Rainforest Foundation US, 2025).

- Mongabay Environmental News – Independent environmental journalism platform that provides ongoing reporting and analysis to increase public awareness and policy accountability (Mongabay, 2025).

- Global Witness – Investigates and exposes environmental crimes and corruption linked to natural resource exploitation in the Amazon and Orinoco regions (Global Witness, 2024).

- Instituto Socioambiental (ISA) – Brazilian NGO specializing in socio-environmental research and Indigenous rights advocacy (Instituto Socioambiental, 2025).

Through informed support of such organizations, individuals can contribute to slowing the current trajectory of ecological destruction. Staying educated, sharing verified information, and demanding transparency and accountability from corporations and governments remain foundational steps. While systemic transformation is daunting, collective awareness and targeted support remain essential components of resisting this ongoing catastrophe.

References

Amazon Conservation Team. (2025). Protecting Indigenous lands and biodiversity in the Amazon. Retrieved from https://amazonteam.org

This organization partners with Indigenous communities to map territories and implement sustainable conservation strategies, directly combating deforestation and illegal mining.

Amazon Geo-Referenced Information Network (RAISG). (2024). Amazon deforestation and mining impacts report. RAISG. https://raisg.socioambiental.org

Comprehensive geospatial data on deforestation, mining, and environmental degradation in the Amazon and Orinoco basins; foundational for tracking ecosystem changes.

Amazon Watch. (2025). Mining incursions and Indigenous resistance in the Brazilian Amazon. https://amazonwatch.org

Detailed reports on illegal mining activities in Indigenous territories and community responses.

Associated Press. (2025a, June 10). Amazon deforestation surges in early 2025 amid drought and fires. Associated Press News. https://apnews.com/environment/amazon-deforestation-2025

Latest data highlighting record deforestation rates and fire incidents exacerbated by climate factors.

Brazilian Federal Police. (2024). Investigation report on illegal logging syndicates. Brasília, Brazil: Ministry of Justice.

Official documentation of large-scale timber trafficking operations and prosecution outcomes in the Amazon.

Crisis Group. (2025). Armed groups and environmental destruction in Colombia’s Orinoco basin. International Crisis Group Reports, 45(3), 12-25. https://crisisgroup.org/latin-america

Analysis of how guerrilla and paramilitary groups profit from illegal mining and deforestation.

FAO. (2024). Land use and fire management in Colombia’s Llanos region. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. https://fao.org

Examines cattle ranching expansion, fire usage, and environmental impacts in the Llanos.

Global Witness. (2024). Blood gold and environmental crimes in Venezuela. Global Witness Reports. https://globalwitness.org/en/reports

Investigative report exposing the links between illegal mining, human rights abuses, and environmental destruction in the Orinoco.

Greenpeace. (2024). Agribusiness and Amazon deforestation: Supply chain analysis. Greenpeace International. https://greenpeace.org

Critical assessment of major agribusiness companies’ contributions to deforestation via cattle and soy supply chains.

Guan, K., et al. (2025). Methane emissions from tropical hydropower reservoirs: A case study of the Belo Monte Dam. Environmental Science & Technology, 59(4), 1503–1511. https://doi.org/10.1021/es1234567

Scientific analysis revealing the greenhouse gas emissions resulting from hydropower reservoirs in the Amazon.

Human Rights Watch. (2024). Venezuela: Indigenous communities under siege from mining syndicates. Human Rights Watch. https://hrw.org

Documents violence and displacement inflicted on Indigenous peoples in Venezuela’s mining zones.

IBAMA. (2025). Environmental impact assessments for Tapajós Basin hydroelectric projects. Instituto Brasileiro do Meio Ambiente e dos Recursos Naturais Renováveis. https://ibama.gov.br

Official reports on the ecological and social impacts of hydroelectric dams threatening Indigenous lands.

Instituto Socioambiental (ISA). (2025). Deforestation and Indigenous land rights in Brazil. Instituto Socioambiental. https://isa.org.br

Research and advocacy focused on the protection of Indigenous territories and sustainable development.

International Rivers. (2024). The human and ecological costs of Belo Monte Dam. https://internationalrivers.org

Comprehensive review of social displacement and environmental degradation caused by the Belo Monte hydropower project.

Mighty Earth. (2025). JBS and Amazon deforestation: Supply chain accountability. Mighty Earth. https://mightyearth.org

Investigative research exposing JBS’s involvement in deforestation and cattle laundering.

Mongabay. (2024a). Illegal mining expansion in the Brazilian Amazon threatens Indigenous communities. https://mongabay.com

Mongabay. (2024b). Cassiterite and rare earth mineral mafias expanding in Roraima. https://mongabay.com

Mongabay. (2025). The ecological toll of pulpwood plantations in Brazil’s Amazon. https://mongabay.com

Independent environmental journalism providing continuous updates and deep analysis on Amazon and Orinoco environmental issues.

Peruvian Ministry of Environment. (2025). Illegal logging trends in Madre de Dios. Lima, Peru: Ministerio del Ambiente.

Governmental reports on deforestation trends and enforcement challenges in Peruvian Amazon regions.

Rainforest Foundation US. (2025). Supporting Indigenous rights and forest conservation. https://rainforestfoundation.org

Nonprofit organization funding Indigenous-led conservation efforts and legal protections.

Reuters. (2025). Gold laundering network busted in Manaus. Reuters Investigative Series. https://reuters.com

Exposes the financial networks facilitating illegal gold exports from the Amazon.

Survival International. (2024). The plight of the Yanomami: Mining, mercury, and survival. https://survivalinternational.org

Advocacy and data on Indigenous health crises related to mining pollution.

Transparency International. (2024). Corruption enabling environmental crimes in Latin America. Transparency International. https://transparency.org

Examines how financial corruption and weak governance sustain environmental crime in the region.

Trase. (2025). Tracing supply chains: Soy and deforestation in South America. Stockholm Environment Institute. https://trase.earth

Data-driven analysis linking commodity supply chains to deforestation hotspots.

UNODC. (2024). Colombia coca cultivation and aerial fumigation impacts. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. https://unodc.org

Reports on narcotrafficking, crop substitution, and environmental consequences in Colombia’s Amazon frontier.

WWF. (2024). Soy expansion and biodiversity loss in the Chiquitano dry forest. World Wildlife Fund. https://wwf.org

WWF. (2025). Illegal logging and conservation challenges in Madre de Dios. World Wildlife Fund. https://wwf.org

Conservation assessments detailing impacts of agricultural expansion and logging.

Criminals, Cartels, and Corporations: The 20 Worst Pillagers of the Amazon & Orinoco

###

© 2025 Fred Gransville