| « American strategists fearing war with Russia | The Triad of Control: AI, Biotech, and the Billionaires Behind the Curtain » |

The Thirsting Earth: From Hunger Stones to Glacier Ghosts in the Age of Collapse

Tracy Turner

Weather lies. Climate kills.

It begins with a misunderstanding. Weather is moody; climate is a movement. Weather shifts like the temperament of a sick king—day to day, tempest to calm, fog to flame. Climate, on the other hand, is the dynasty behind the throne, grinding empires to dust over centuries or—more recently—decades. Mistake one for the other and you might bring an umbrella to a mass extinction.

As the world fixates on momentary heatwaves or polar vortex novelties, a planetary contraction is underway—a slow-motion implosion of water, soil, food, shelter, and trust. Drought is not merely an agricultural inconvenience. It is a planetary verdict. It is not local; it is global. It is not temporary; it is systemic.

The Thwaites Doomsday Glacier

The Doomsday Glacier is cracking from the inside out. Recent May 2025 data shows the Thwaites Glacier is splintering at nearly 3 meters per day—not due to melting, but from internal destabilization. Its Eastern Ice Shelf is in a final death spiral, with widening cracks no longer tied to ocean warmth but to mechanical collapse. The potential fallout? A 65 cm sea level rise if Thwaites goes. Worse, it could unleash the West Antarctic ice sheet, driving oceans up by 3.3 meters and submerging coastlines worldwide. Its grounding line rests below sea level, making it vulnerable to warm seawater and locked in a feedback loop of self-destruction. This is not slow melt. This is structural failure. A planetary pressure point snapping in real time.

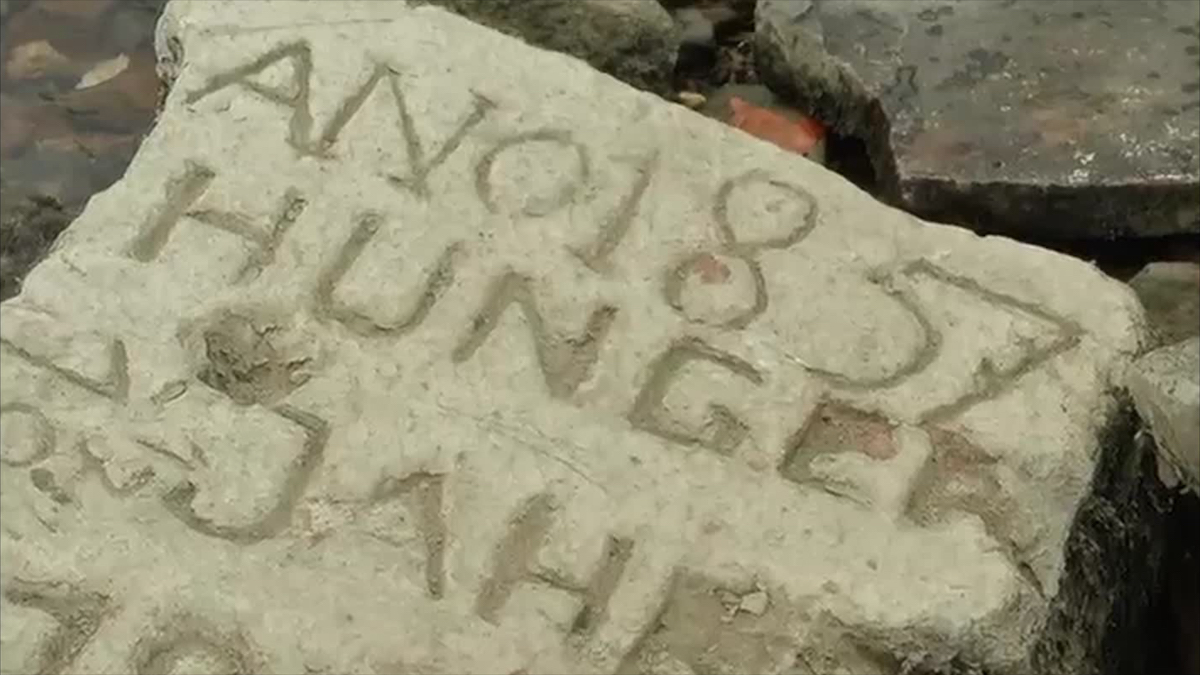

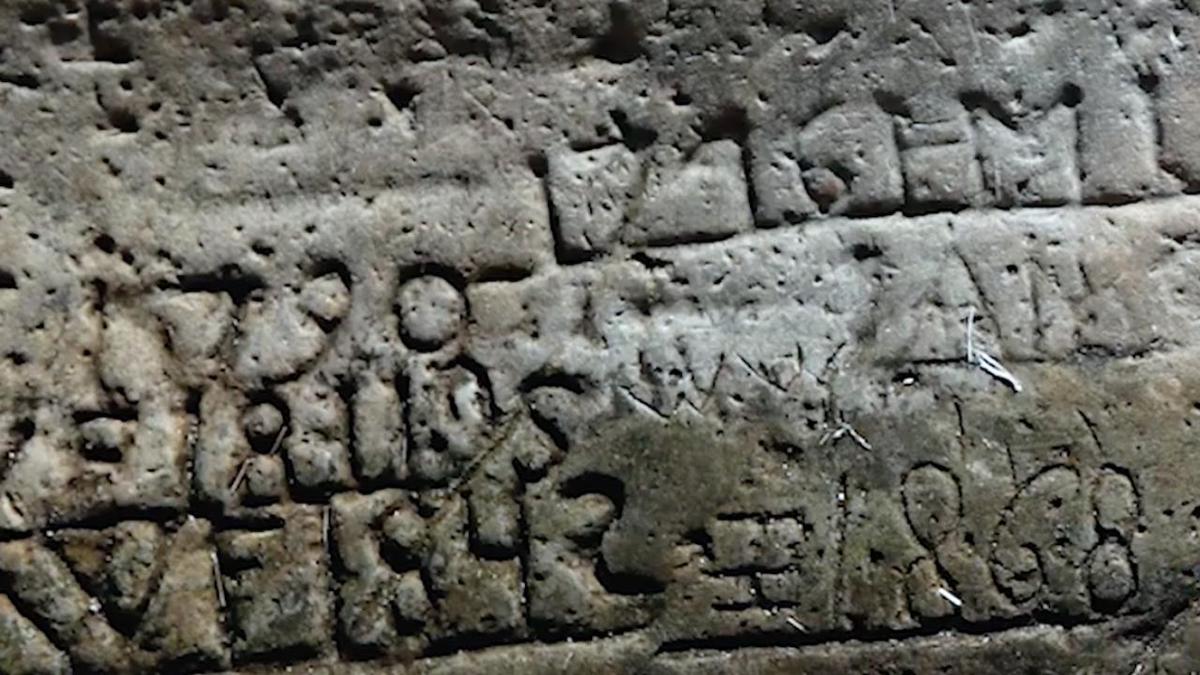

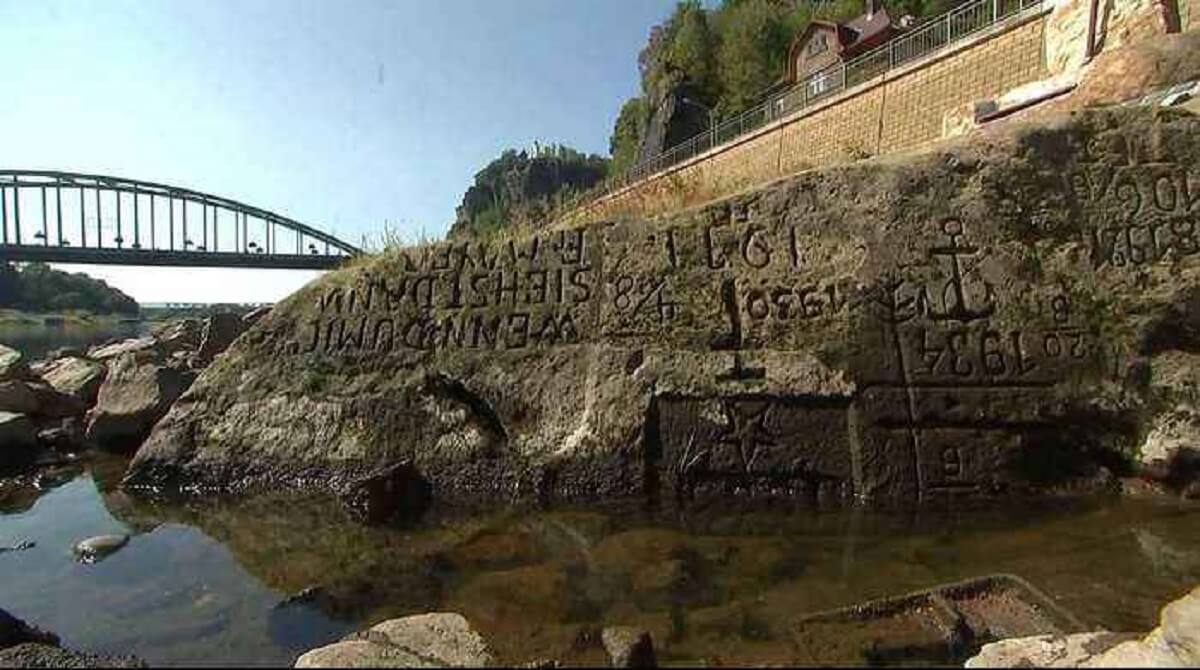

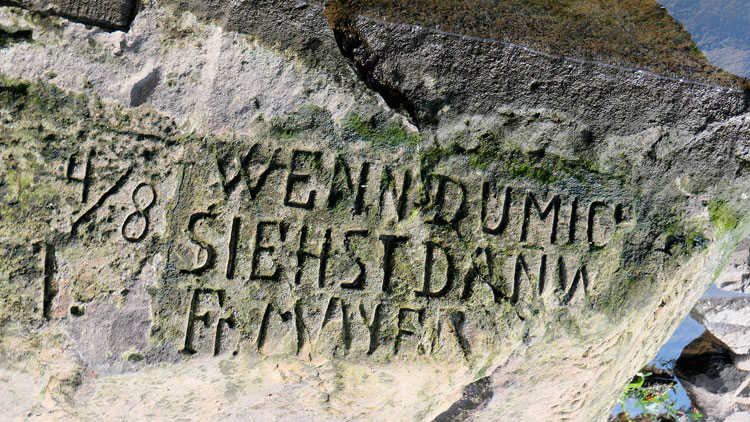

From the Mississippi to the Mekong, the Loire to the Tigris, rivers are vanishing. Hunger stones—centuries-old hydrological tombstones—are surfacing again, mocking us with their carved warnings: “If you see me, weep.” Glaciers, those frozen libraries of Earth’s past, are bleeding into oceans that are rising—and losing their salt. Yes, losing their salt. Freshwater now flees from mountains, forests, and farms into the sea like a silent exodus, diluting the ancient saline bloodstream of the planet.

The consequences are biblical in scale and banal in disguise: insurance contracts canceled, mortgages denied, farms foreclosed, grocery shelves shrunk, towns de-zoned, homes uninsurable, lives unlivable. While policy wonks talk of “adaptation” and tech moguls dream of Martian exodus, millions on this planet quietly ration water, abandon land, and bury livestock.

But this may be just the overture. The strange paradox of the climate crisis is that runaway warming may not end in heat—it may end in ice. A new glacial epoch, triggered by the very meltwaters of our current excess, lurks not in science fiction but in sediment cores and satellite maps.

In 2022, numerous news authors warned of hunger stones and hydrological omens. Three years later, the signs are louder, crueler, and more final. This article is an attempt to trace the outline of this collapse—not through hysteria, but through hard evidence, geography, economics, and the slow scream of climate history repeating itself, only hungrier.

Part 1: The Vanishing Veins of the Planet

Rivers are not just waterways. They are arteries of civilization, veins of commerce, culture, and sustenance. And now, they are vanishing—not metaphorically, not gradually, but visibly, drastically, and with stunning simultaneity.

In Europe, the Rhine, Po, and Loire rivers have shrunk to trickles, stalling cargo traffic, collapsing hydroelectric output, and exposing long-forgotten relics: bombs from World War II, ships from the Napoleonic era, and the now-infamous hunger stones, grim epitaphs carved during ancient droughts. These engraved rocks, some dating back to the 15th century, speak in chilling minimalism: “When you see me, cry.”

Across the Atlantic, the Mississippi River, a backbone of American transport and agriculture, saw its lowest levels in decades, grounding barge traffic and forcing emergency dredging. In China, the once-mighty Yangtze has been choked by drought so severe that the Poyang Lake, China’s largest freshwater body, contracted to barely a puddle, crushing fisheries and endangering nearby ecosystems.

And in Africa, Lake Chad, once a shimmering expanse supporting 30 million people across four nations, has shriveled by over 90% since the 1960s. A similar fate afflicts the Aral Sea, a former inland sea in Central Asia now reduced to a toxic salt pan, its ghost ports stranded miles from any shore.

These aren’t isolated cases—they are a global pattern of hydrological retraction, the Earth’s aqueous circulatory system seizing under the twin pressures of climate volatility and human overuse.

Image Gallery: Global Drought & Dry Rivers

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

“The world’s rivers are drying up at the fastest rate in 30 years,” reports a 2024 hydrological review, warning that even non-arid regions like the UK and Germany are no longer exempt from freshwater collapse.

The Spread of Drought: Not a Fluke, But a Forecast

Drought used to be cyclical. Now it’s perpetual, compound, and self-reinforcing. Regions are no longer recovering before the next dry siege begins. California, for instance, swings wildly between megadrought and megaflood, a volatility amplified by rising atmospheric water vapor. In the Horn of Africa, drought now devours the same areas year after year, turning entire nations into hydro-orphans.

In South America, the Amazon basin, long regarded as Earth’s green lungs, is now under siege from both deforestation and a climate-triggered drying trend. Parts of the Madeira and Negro rivers are at their lowest recorded levels, strangling both biodiversity and indigenous subsistence.

And yet, the bureaucracies in Washington, Brussels, and Beijing treat drought like a budgeting anomaly—something to “mitigate,” not something that dictates the terms of planetary survival.

Glaciers: Bleeding Giants of the Cryosphere

The rivers, of course, come from somewhere. Glaciers, once monolithic guardians of planetary freshwater, are now hemorrhaging. In 2024, scientists confirmed that every one of the world’s 19 glacier regions experienced net mass loss for the third year running. These frozen lifelines, feeding the Ganges, Indus, Colorado, Rhône, and countless others, are being sacrificed on the altar of a few decades of industrial recklessness.

More than 1.9 billion people rely on glacier-fed water. That number may soon become meaningless—not because populations will shrink, but because the glaciers will disappear.

"We are watching the liquidation of planetary savings accounts," noted a glaciologist from the World Meteorological Organization, “with no plan for what happens when the vault is empty.”

As glaciers melt, they do not evenly replenish water cycles. Instead, they accelerate sea-level rise, inject low-salinity water into the oceans, and disrupt thermohaline circulation—the planetary conveyor belt of ocean currents that regulates weather, temperature, and precipitation on a global scale.

Part 2: Ocean Salinity, Climate Instability, and the Icefire Paradox

Beneath the surface of our rising seas, another transformation is underway—one less visible but no less deadly. The world ocean, that ancient basin of brine and balance, is losing its salt.

It sounds counterintuitive—how can the oceans become less saline as the planet heats? Yet this is precisely what’s happening. As glaciers and inland freshwater reserves melt, they dump vast quantities of low-salinity water into the sea. This dilution of ocean salinity threatens to cripple one of the Earth’s most vital systems: the thermohaline circulation, also known as the global conveyor belt.

NASA scientists observed in 2024 that El Niño events combined with accelerated polar melt had caused noticeable drops in coastal salinity, particularly along the Pacific Rim and North Atlantic seaboard.

This shift has deep, destabilizing consequences. The thermohaline system—driven by gradients in temperature (thermo) and salinity (haline)—controls the flow of warm and cold currents across the planet. Disrupt it, and you disrupt monsoons, storm systems, fisheries, arable zones, and even the global carbon cycle.

From Warming to Freezing: The Climate Reversal Trap

And herein lies the Icefire Paradox—that runaway global warming might not end in perpetual heat, but instead, tip the Earth into a new Ice Age.

This is not science fiction—it’s geological history. In previous interglacial periods, massive glacial meltwater pulses led to abrupt cooling events by shutting down the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC). Such shutdowns triggered multi-century freezes, desertification, and global crop collapse.

“We are not just melting ice,” warns climatologist Dr. Samir Younes, “we’re tampering with the planetary thermostat.”

If the AMOC were to collapse, Europe could plunge into frigid winters, tropical regions could dry out catastrophically, and entire breadbaskets could vanish. Sea levels might rise faster on some coasts and fall on others, further destabilizing human settlements.

It’s a climate roulette wheel—spin it with fire, land on ice.

Hunger by Fire or Hunger by Frost

Regardless of the path—scorching heat or global freeze—the outcome is the same: hunger.

Global warming is already destroying food systems through drought, heatwaves, wildfires, and soil degradation. But a sudden cold snap—even a regional one—would obliterate harvests unaccustomed to frost, especially in monoculture zones.

In 2023 alone, over 345 million people faced acute food insecurity, according to the World Food Programme. That number is rising, not falling. Climate-triggered hunger doesn’t discriminate by politics or geography. It radiates outward—faster than we can adapt, faster than crops can evolve.

And food contraction has a domino effect: livelihood contraction, displacement, violence, and the disintegration of social contracts. You cannot vote your way out of an empty stomach.

Farms, Fire, and the Flickering Future

As drought spreads and rivers vanish, so too does arable land. Once-reliable breadbaskets are withering into dust. The U.S. cattle herd is shrinking, farmers are abandoning fields across Sub-Saharan Africa, and Australia’s agricultural zones are migrating southward, inch by inch, like climate refugees with no passport.

This is not just farm contraction. It is a civilizational contraction. And it echoes into mortgages, insurance, housing, and infrastructure—topics rarely linked to climate until it’s too late.

Part 3: Housing, Insurance, and the Shrinking Map of Survival

In a sane world, climate collapse would trigger a mass mobilization—new migrations, new policies, new paradigms. Instead, we are witnessing the reverse: contraction, exclusion, and the slow bureaucratic erasure of people deemed "too risky to cover."

It begins quietly. Insurers pull out of high-risk zones—California, Florida, parts of the Gulf Coast—no longer willing to underwrite homes in the path of fires, floods, and hurricanes. Then come the mortgage denials. Without insurance, banks refuse to lend. Without loans, homes can’t be bought. Without buyers, entire towns die.

“The housing market collapse won’t look like 2008,” noted a 2025 report by the International Climate Risk Council. “It will look like foreclosure by nature.”

And this isn't just about beachfront condos or desert subdivisions. Urban cores are at risk too. Rising heat indexes, collapsing power grids, and failing water systems are rendering cities uninhabitable by degrees—both figuratively and literally.

Insurance Collapse = Livelihood Collapse

Without insurance, there is no security. Without security, there is no economic participation. As more regions are designated uninsurable, business investment dries up, residents flee, and governments retreat—leaving only ghosts and scavengers behind.

This is not speculative. In Louisiana, entire parishes are seeing insurance premiums triple or disappear entirely. In Bangladesh, floodplain communities are being permanently evacuated, with no plan for permanent relocation or compensation. Even in Europe, insurers are quietly blacklisting regions hit by repeat climate disasters.

Meanwhile, governments and private firms alike engage in quiet triage, deciding which regions to save and which to abandon to the elements.

A Shrinking World with Fewer Places to Live

As freshwater shrinks, farmland burns, and insurers flee, the global map of viable human settlement is collapsing inward. The habitable world is shrinking. And with it, so too is the idea of a secure life—a house, a job, a future.

In 2024, the UN warned that 1.2 billion people could be displaced by climate-related instability by 2050—a number so massive it overwhelms imagination but not markets.

The investor class is already moving. Tech elites buy bunkers in New Zealand, hedge funds invest in Arctic farmland, and governments pour money into climate fortress cities, complete with perimeter defenses and water sovereignty laws.

But for the global poor—and even the middle class—there is no Plan B. There is only eviction by entropy.

The Planet is Not Broken. The System Is.

What we are witnessing is not a natural disaster. It is a structural unraveling. A system built on perpetual expansion is collapsing into climate-imposed limits, and rather than adapt collectively, it is choosing triage, hoarding, and abandonment.

“We are not running out of water,” wrote geographer Dr. Alejandra Velez, “we are running out of access.”

That distinction matters. Because it means the future is not just hotter—it is more unequal, more violent, and more fragile than anything our economic models can compute.

Part 4: The Politics of Collapse and the Failure of Forecasts

If drought and flood are the symptoms, denial is the disease. While rivers dry and oceans dilute, the world’s political classes sip from bottled water and quote GDP forecasts. Collapse isn’t coming, they assure us—it’s “being managed.”

But what exactly is being managed? Certainly not water tables, crop failures, or mass displacement. What’s being managed is optics—the illusion of control as the planet’s life-support systems blink red.

“Forecasts have become rituals,” notes political ecologist Mira Adan. “They’re designed less to predict than to sedate.”

Indeed, each year, new climate reports offer timelines, ranges, and projections—all hedged in language like “uncertainty”, “possible futures”, and “model variability.” But on the ground, the variability is gone. It’s happening, and faster than anyone officially predicted.

The Permanent State of Emergency

In response, governments have quietly begun to institutionalize crisis. What was once the realm of emergency declarations—like wildfire evacuations or water rations—is now standard policy. Entire states operate under perpetual drought conditions. Climate disaster funds are no longer temporary reserves—they’re annual line items.

This normalization of catastrophe serves a dual purpose: it shields governments from accountability and conditions populations to accept deprivation as the new normal.

And yet, while climate chaos spreads, political frameworks remain frozen. Electoral cycles, budget structures, and zoning codes still function as if the 20th century never ended. Modern democracies were built for economic growth—not contraction. And so, they buckle under the weight of a reality they cannot legislate away.

Media as Sedative, Not Signal

Mainstream media outlets, still addicted to event-based reporting, fail to capture the systemic nature of the crisis. A wildfire here, a flood there, a crop loss in passing. But what is rarely shown is the unfolding global latticework of collapse—how rivers, farms, homes, and hospitals are all connected by climate threads now snapping simultaneously.

And so, the average viewer, even when concerned, is left with fragmented anxiety, compartmentalized horror, and no sense of totality.

“We are not in the Anthropocene. We are in the Absurdocene,” quipped one climate philosopher. “An age where we know everything and act on nothing.”

The Mirage of Technofixes

In this vacuum, the techno-utopian class steps forward with its salvation mythology: carbon capture, space mirrors, desalination, AI weather modeling, synthetic food. But none of these tools—even if deployed perfectly—address the fundamental issue: a system of perpetual growth on a finite, dying biosphere.

These technofixes, like modern monetary theory for natural limits, presume the continuation of the unsustainable, rather than a reckoning with it. They are offered not as tools of justice, but as escape hatches for the wealthy—from bunkers to Martian colonies.

“Geoengineering is not a solution,” warns Iranian climatologist Soraya Kashani, “it is a confession of failure.”

Hope is a Discipline, Not a Feeling

If collapse is systemic, so must resistance be. But that begins with telling the truth—not in whispers or scientific white papers, but loudly, publicly, and without euphemism.

Hope, if it is to exist, must be earned—not felt. It is a discipline of action, not a sentiment of denial. And that action begins not with greenwashed policy or tech fetishism, but with the naming of collapse, the sharing of water, and the refusal to abandon the vulnerable to the tides.

Part 5: Echoes of the 2022 Warning — Hunger Stones, Civilization, and the Final Ledger

In 2022, many prophetic voices detailed the synchronous vanishing of rivers across five continents, the collapse of the Colorado basin, the crackling desolation of Lake Mead and the Yangtze, and the dire omen of hunger stones rising from the depths like tombstones for modernity.

“The rivers have spoken; the old bones of empire now break the surface.”

This warning was not just about rivers or crops—it was about civilization’s immune system failing. We foresaw the emerging picture as a death spiral of ecological thresholds, economic denial, and psychological fragmentation. A planetary tipping point not into chaos, but into inversion—where wealth breeds scarcity, technology breeds ignorance, and progress becomes pathology.

And now, just three years later, every forecast has metastasized.

The Hunger Stones Are Everywhere Now

Once limited to drought-scarred riverbeds in Europe, the hunger stones—carved with desperation and curses—have become a global symbol. In the Mekong. In the Tigris. In the Paraná. Even in the Rio Grande. Wherever water recedes, a message reemerges from the past:

“If you see me, weep.”

But what was once a local cry is now a planetary eulogy. The Earth itself is engraving the message. The shrinking glaciers, the silent reservoirs, the cracked deltas—all are warnings in a language older than speech and more final than prophecy.

This is not just environmental degradation. It is the unraveling of place, the collapse of livable geography. The map itself is dying. Not just rivers, but roads, crops, housing, law, and culture—all depend on water. And now, that water is being taken back by the sky—or vanishing into corporate bottling plants and military desalination machines.

Civilization's Scorecard: A Dead Ledger

To assess civilization today is to open a ledger of delusions:

- Freshwater: 87% of global freshwater is already allocated, mostly to industry and agriculture. What remains is being privatized or lost.

- Arable land: Over 33% is degraded beyond use. Desertification now spreads faster than reforestation.

- Insurance: Pulling out. Mortgages: Declining. Resettlement plans: Nonexistent.

- Atmosphere: +1.5°C and rising. CO₂ past 425 ppm. Methane spiking. Feedback loops engaged.

- Glaciers: Bleeding. Rivers: Dying. Oceans: Acidifying and desalinizing.

- Livelihoods: Eroding. Governments: Prepping bunkers, not recovery.

This is not a cycle. This is a collapse vector.

What the Stones Could Not Carve

The hunger stones carved their truth in rock because paper rots and power lies. They had no modeling software, no policy journals, no think tanks. Just the chisel and the riverbed. And yet they understood something we refuse to:

Collapse is not a singular event. It is a long descent through thresholds society refuses to name.

We are beyond drought now. We are in the realm of livelihood contraction, territorial triage, infrastructural unmaking, and mass moral failure. And still, the global North speaks of innovation, GDP targets, and techno-salvation, while those in the South walk miles for evaporated wells.

If there is redemption, it will not come from Silicon Valley or Davos. It will come from communal survival, from local reclamation, from people who still know what water is worth, what soil means, what community requires when the grid goes silent.

Final Tally: Not the End of the World — Just the World as We Knew It

So, this is the ledger. Not apocalyptic, but terminal. Not fire and brimstone, but dust and silence. The end of abundance. The return of hunger. The inversion of all that was once promised by empire and extraction.

We are not powerless. But we are out of time.

The riverbeds have spoken.

The glaciers are bleeding.

The hunger stones have risen.

And we would do well to listen before they fall silent again.

If You See Me, Weep: The Return of the Hunger Stones

In the parched summers of Central Europe, as rivers draw back their ancient veils of water, a strange chorus of stone voices rises from the depths. Carved centuries ago, sometimes as far back as the 15th or 16th century, these so-called “hunger stones” emerge not only as geological artifacts but as historical oracles—grim, moss-streaked monuments that whisper warnings to those who will listen. “Wenn du mich siehst, weine,” reads one of the most infamous. “If you see me, weep.”

In the drought-plagued year of 2022, these stones surfaced again, most famously in the Elbe River near the Czech town of Děčín. Their reappearance captivated the public imagination, and the press took notice. From wire services like the Associated Press to weightier essays in European publications, a new generation was introduced to these melancholic markers of misery. They are not just hydrological curiosities but relics of famine memory—etched by hands long dead, warning of consequences humanity has repeatedly chosen to forget.

Historically, their message is simple but profound: water is life, and its absence foretells hunger, upheaval, and despair. Each re-emergence is not just a hydrological accident but an intergenerational telegram, delivered in granite, bearing news from past catastrophes. And in this age of melting glaciers and vanishing rivers, such telegrams demand attention.

By 2023 and into 2024, the hunger stones have not entirely receded back into obscurity. The media, ever hungry for symbols that bridge climate change and historical resonance, has continued to evoke them—though perhaps not with the same fervor as during the scorched news cycles of 2022. Their coverage persists, but subtly, as part of a broader conversation about drought, disaster, and the long memory of stone.

In that sense, the hunger stones have transcended mere historical curiosity. They have become climate monuments—not erected but revealed. Not prophetic in their creation, but prophetic in their recurrence. And like the old maps that warned “Here be dragons,” these stones speak not of mythical dangers but of very real ones: drought, starvation, the collapse of order.

To see them is to be reminded that history is not past. It is merely submerged—until the water falls away.

Global Drought Situation: 2023, 2024, and Expected for 2025

2023:

- Pervasive and Deepening: The droughts became more frequent and severe globally, impacting ecosystems, economies, and livelihoods heavily.

- Vulnerable Communities Affected Most Severely: Developing countries, particularly rural populations with poor water resources, were impacted most severely.

- Impacted Key Regions: Horn of Africa, Sahel, Madagascar, Argentina, Chile, Iran, Central Asia, Europe (with its hottest summer and second-warmest year ever), and North and South America (in particular).

- Human-Induced: Human-induced climate change was identified as a major driver making droughts more severe.

2024:

- Continuing Extremes: The world experienced fresh temperature records and additional precipitation extremes, aggravating water-related risks like droughts.

- Amazon Basin and Southern Africa: These areas were hit by serious drought, which resulted in record-low water levels in the Amazon and widespread food shortages and power rationing across Southern Africa.

- North America: Mixed conditions, with conditions improving in some areas and worsening in others, particularly the Northern Plains, Lower Colorado River Basin, and Far West Texas/southern New Mexico, which finished the year in exceptional to severe drought. Record dryness was experienced in the contiguous U.S. for October.

- Global Impacts: The droughts threatened crop yields and energy production, resulting in severe economic loss and population displacement.

Expected in 2025

- Increased Risks: 2025 forecast indicates a continued risk of worsening droughts in most regions.

- Greatest Areas of Concern: Northern South America, Southern Africa, northern Africa, Central Asia, parts of North America, and Western Australia will probably experience new or reoccurring droughts.

- Repeated Dry and Warm Weather: In general, dry and warmer-than-average weather is expected to persist in most of the affected areas, placing extra stress on water resources.

- Africa: Severe drought is expected to persist and strengthen in some of central, northwest, and northeast Africa, impacting agriculture, ecosystems, and hydropower.

- United States: Drought persistence is expected across much of the western and eastern United States, with some potential relief in parts of the central and southern Plains. Drought development is expected north of Lake Okeechobee, Florida. Drought persistence is expected in California and Nevada, with potential impact on water supply and wildfire danger.

Generally, the world is seeing an increase in the number and intensity of occurrences of drought due to climate change, which has profound humanitarian, environmental, and economic impacts.

Sources:

Climate Change & Drought

1. Cook, B. I., Mankin, J. S., & Anchukaitis, K. J. (2018). Climate change and drought: From past to future. Current Climate Change Reports, 4(2), 164-179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40641-018-0093-2

2. Williams, A. P., et al. (2020). Large contribution from anthropogenic warming to an emerging North American megadrought. Science, 368(6488), 314-318. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaz9600

3. United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD). (2022). Drought in numbers 2022. https://www.unccd.int/resources/publications/drought-numbers

Glacier Retreat & Water Scarcity

4. Huss, M., & Hock, R. (2018). Global-scale hydrological response to future glacier mass loss. Nature Climate Change, 8(2), 135-140. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-017-0049-x

5. Milner, A. M., et al. (2017). Glacier shrinkage driving global changes in downstream systems. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(37), 9770-9778. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1619807114

6. Zemp, M., et al. (2019). Global glacier mass changes and their contributions to sea-level rise from 1961 to 2016. Nature, 568(7752), 382-386. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1071-0

Hunger Stones & Historical Droughts

7. Brázdil, R., et al. (2019). Droughts in the Czech Lands, 1090–2018 AD. Climate of the Past, 15(3), 827-849. https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-15-827-2019

8. Pfister, C., & Wetter, O. (2011). The worst droughts in Europe since the Middle Ages: A hydrological perspective. PAGES News, 19(1), 16-17. https://doi.org/10.22498/pages.19.1.16

Ocean Salinity & AMOC Collapse Risk

9. Caesar, L., et al. (2021). Current Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation weakest in last millennium. Nature Geoscience, 14(3), 118-120. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-021-00699-z

10. Durack, P. J., et al. (2012). Ocean salinities reveal strong global water cycle intensification from 1950 to 2000. Science, 336(6080), 455-458. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1212222

Insurance, Housing, & Climate Risk

11. Kousky, C. (2019). The role of natural disaster insurance in recovery and risk reduction. Annual Review of Resource Economics, 11, 399-418. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-resource-100518-094028

12. Hino, M., & Burke, M. (2021). The effect of information about climate risk on property values. PNAS, 118(17), e2003374118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2003374118

Food Security & Agricultural Collapse

13. Lesk, C., Rowhani, P., & Ramankutty, N. (2016). Influence of extreme weather disasters on global crop production. Nature, 529(7584), 84-87. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature16467

14. FAO. (2023). The state of food security and nutrition in the world 2023. http://www.fao.org/state-of-food-security-nutrition

Media & Climate Communication

15. Boykoff, M. T. (2019). Creative (climate) communications: Productive pathways for science, policy, and society. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108164047

16. O’Neill, S., & Nicholson-Cole, S. (2009). “Fear won’t do it”: Promoting positive engagement with climate change through visual and iconic representations. Science Communication, 30(3), 355-379. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547008329201

- Associated Press. (2022). Drought reveals ancient 'hunger stones' in European river. Retrieved from https://apnews.com/article/9512be71cc8f40a7b6e22bc991ef2c6c

- Al Jazeera. (2022). ‘If you see me, weep’: Hunger stones auguring drought in Europe. Retrieved from https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2022/11/29/if-you-see-me-weep-hunger-stones-auguring-drought-in-europe

- Le Monde. (2022). 'Hunger stones' resurface across Europe as a warning from droughts past. Retrieved from https://www.lemonde.fr/en/environment/article/2022/08/20/hunger-stones-resurface-across-europe-as-a-warning-from-droughts-past_5994193_114.html

- The Guardian. (2022). Hunger stones, wrecks and bones: Europe’s drought brings past to surface. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/aug/19/hunger-stones-wrecks-and-bones-europe-drought-brings-past-to-surface

The Thirsting Earth: From Hunger Stones to Glacier Ghosts in the Age of Collapse

###

© Tracy Turner